B-ai-ck 2 School

Op-Ed by Kristian Redhead Ahm, Assistant Professor in Media Production & Management – Danish School of Media and Journalism (DMJX)

/Promptcollective is back — notebooks open, pencils sharpened, and tabs full of LLM experiments. What better way to get back in gear than with a guest op-ed from someone who’s knee-deep in the realities of AI in education?

Kristian Redhead Ahm, assistant professor at DMJX, drops in with an honest, nuanced look at what happens when generative AI meets real students, real syllabi, and very real uncertainty. This is a field report — from classrooms where ChatGPT, Perplexity, and DALL·E are being folded into academic life, for better and worse.

When is AI a powerful creative catalyst? When is it just a shortcut that robs students of growth? And how do we teach reflection in a world built for convenience?

Read on, buckle up and prepare to feel smarter — or at least more constructively confused.

Guest Op-Ed: On Generative Artificial Intelligence and the Bachelor’s Program in Media Production and Management

By Kristian Redhead Ahm, Assistant Professor in Media Production & Management – Danish School of Media and Journalism (DMJX).

I will do my best to be as prosaic and specific as I can in this op-ed. Since

the op-ed is a relatively open genre, I will take advantage of it to express myself

very freely. Perhaps even boringly. At the time of writing, I am in the middle of a

research project at the Danish School of Media and Journalism (DMJX), where we

are investigating the use of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) in the Danish

creative industries. In connection with communicating the research findings, I will

adopt a more professional tone. However, with this text, I want to address the topic

“GenAI and Education” in as downplayed a manner as possible. I apologize

in advance.

I believe that the way we arrive at what GenAI will actually mean across the contexts

of the media industry, is by trying to describe our experiences with it as precisely as possible. That gives us a language to evaluate its usefulness. I use GenAI myself in my work as an assistant professor in Media Production and Management at DMJX. I

have created a custom GPT in ChatGPT, which I trained on several pedagogical

texts that inform my own teaching practice. If I’m unsure how to structure a three-hour

teaching day, with time for exercises, reflection, and presentations, GenAI can give me a prompt that I then develop further. It’s significant to have such a specific idea generator at your fingertips day and night. It’s a useful tool.

A text as boring as the paragraph above, I believe, is the way we avoid dystopian and

utopian visions of GenAI. It is a technological tool that can be used responsibly or irresponsibly in specific situations. However, the negative consequences of irresponsible use are greater than anything I have seen before. Not only in relation to the creation and spread of disinformation, but perhaps worst of all, if a user of GenAI believes they are being presented with bulletproof information. That is not the case. The user of GenAI is presented with a probable answer to their prompt. Truth, at the time of writing, plays no role for the large language models.

In the following, I will describe some experiences I have had in connection with a fairly liberal rollout of GenAI in the 1st semester of the bachelor’s program in Media Production and Management. None of what I am about to describe is a testament to good or bad usage of GenAI; it is simply what I experienced. After my presentation of what happened, I will offer some general reflections.

Responsible use of AI

Together with a colleague, we decided in the summer of 2024 that we would introduce the new students in the program to the responsible use of GenAI, with the intention that not only could they use it in their studies, but they should. We introduced tools like ChatGPT and Copilot, among others, as an extra group member that could help with idea generation, as a helpful editor, or as a tutor that could explain complex concepts in more tangible terms. We made it clear that it was not meant to replace their work and study processes but to support them. I am still convinced that these tools can do this.

I teach a very academic subject in the 1st semester called Media Industries in Transition. There’s nothing unusual about new students at a higher education institution finding it difficult to read English-language research literature, even when they find the topic interesting. In that context, I introduced them to NotebookLM, developed by Google. With NotebookLM, they can upload their PDFs and have a conversation with their syllabus as if it were a human. Here we return to one of the things I find magnificent about the technology: that the raw, rugged information landscape that any research article is can be humanized and explored in a

dialogical way— that’s new and significant. At this point in the course, I have introduced the students to academic reading. It may sound advanced, but it’s just about first scanning and skimming the text, writing down questions along the way, and then carrying out the detailed reading sentence by sentence. I introduced NotebookLM as a supplement to these reading processes, not as a replacement. It could give them a superficial understanding of the text in seconds, supporting their detailed reading. The obvious risk is this: What if they never progress beyond

the superficial understanding? I find that it’s difficult for many students to view texts not simply as repositories of information but as catalysts for their own reflection and idea development. Here, I fear that GenAI can do more harm than good if introduced too early to students.

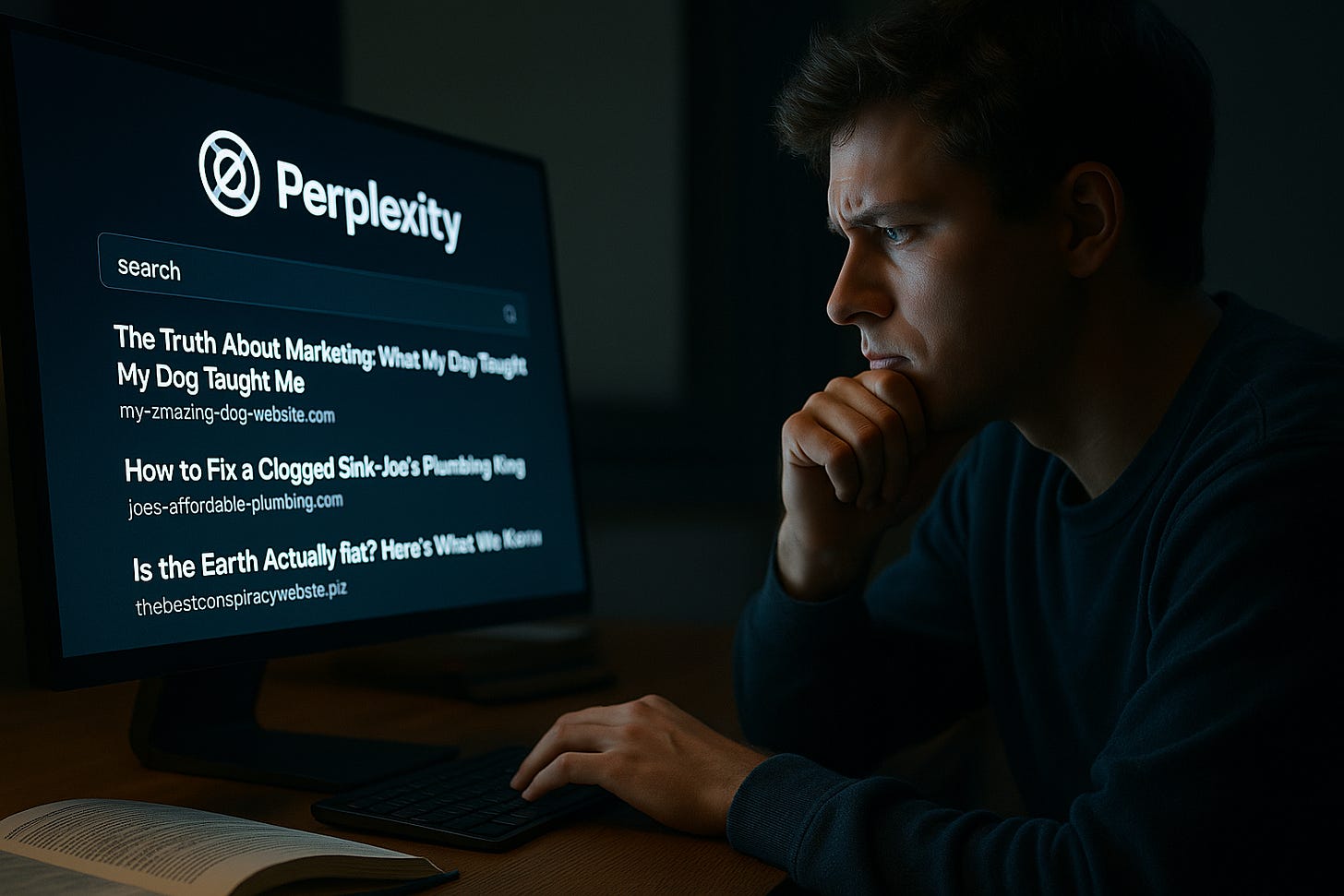

Perplexity and the Problem of (Over)Confidence

In the same course, I introduced the students to Perplexity, a GenAI that functions like a search engine. It was a predominantly negative experience, as it turned out that the tool was not capable of assessing the quality of the sources it presented to the students. It is configured to present a summary of the search results with an authoritative tone, even when the sources it refers to are of very poor quality. This had direct negative consequences for some students’ exam papers. For instance, a key concept like marketing was defined with references to private individuals’ blogs or company websites that served as covert advertising for their services,

instead of sources of high quality such as research literature or respected professional sources. Perplexity commits the serious error of, firstly, not understanding the difference between research and everything else on the internet and, secondly, presenting its flawed sources in a strongly authoritative, superficially convincing voice. It is important to note that these dubious information sources were included even when my students and I, in the prompt, asked for verifiable sources that had undergone a peer-review process. Perplexity is, at the time of writing, a windbag machine. Based on these experiences, in which the students unfortunately, even after three years of high school, possess very limited critical source evaluation skills, Perplexity has a harmful impact on the development of the students’ independence and reflective abilities. They trust the output too much.

The above makes me aware of how exceptionally important it is, as early as possible in a person’s formation—inside or outside the education system—to give them knowledge of and experience with seeking out and assessing the quality of information sources. With and without GenAI. Not exactly a revelation of epic proportions. Around minute 49 of an interview on the Louisiana Channel from 2021, Lars von Trier argues that children should already be taught

Media Studies in the first grade. “There are so many ways of manipulating, that it’s crazy […]” (said at minute 49:13–49:18. This is, by the way, a kind of source reference

so you can check if he actually said what I just wrote. I have a feeling that good references will become quite important in the future.) I would normally never contradict Lars von Trier in a public forum, but here I would like to argue that Media Studies should begin in preschool. With all due respect.

Inspiration by Algorithm

As a small surprise, I will now tell you about a positive experience I had with including GenAI in the 3rd semester of the bachelor’s program. In the 3rd semester, I teach interface design, where students must either redesign an existing website for an organization or design one from scratch if the organization needs one. In this course, I dedicate a couple of hours, three weeks into the course, to let the students generate images with the GenAI tool DALL-E. This takes place in the week when the students are just beginning to make aesthetic decisions about the color palette, typefaces, image style, etc., for their website. In the weeks prior, they have defined a

creative brief, developed a concept, and made wireframes of the interface. The point is not for the generated images to be included in the high-fidelity prototype they submit for the exam. Rather, the idea is for them to be inspired by the images that appear before their eyes. The GenAI -generated image is intended as a catalyst for their own ongoing, divergent idea development. Here we return to one of the remarkable things about GenAI. The possibility of generating extremely specific images is extremely useful for exploring multiple visual solution proposals in a short period of time. However, this presupposes that the students already have an

understanding of what they want to create. That is why I only show them the tool three weeks into the course. One of the groups generated an image of a sunset. The shades of purple, pink, and dark blue inspired the color palette that ended up being used in their final prototype. For other groups, the inspiration was more diffuse. One group generated a moody image of a wine bar, which gave them a fundamental feeling for the atmosphere they wanted on their website. An intimacy and mystique they had difficulty articulating became clearer when they encountered GenAI’s random, yet tailored output.

The Beautiful Struggle - How GenAI risks stealing something essential from the learning process

Now I will discuss the implications of what was observed. I think it’s crucial to consider when students are introduced to and encouraged to use GenAI. This can be in the context of a specific course, or across the entire program. If they are introduced too early, there is a real risk they will use the tool too much as an information source, which it is not. Or that they will be overly nudged and pivoted by its ideas. GenAI can be used to get a tailored yet unexpected input that can inspire and push students out of locked thought and action patterns. Yet this requires them to already have a

fundamental technical and professional identity on which they can rely. A foundation that allows them to relate critically and in a subject-relevant way to the output.

When I compare the behaviour of the students in the 1st semester to the 3rd semester, I notice an important difference in how they relate to the output. The older students by this point have a nascent professional identity, which gives them the basic understanding of what is useful and not useful in the output. Most of the older students understand that the output can be a valuable tool in an early, exploratory phase of a creative project. Most importantly, they understand that the convergent decision-making phase—where the output is curated and evaluated—is their work and theirs alone. As human beings, with brains and stomachs and nervous systems, etc., they can make a decision that collapses a giant field of possibilities into a single point.

GenAI can make a thousand suggestions if asked, but it cannot make an informed decision about which proposals are worth pursuing. Another important aspect reflected in the difference between my two examples is whether the truthfulness of the output matters. This was clearly a problem in the academic course in the 1st semester, where it hallucinated or did not understand the quality difference between sources. But in the creative subject in the 3rd semester, where students are only encouraged to use it for visual idea development, hallucination is the whole point.

When my colleague and I decided to try a very liberal rollout of responsible GenAI usage, it was based on the assumption that GenAI usage would become a whole new fundamental competency that our students must learn to navigate the future media industry. After our experiences in the 1st semester, we have decided to pull back a bit on this liberal approach to GenAI. It should not disappear—that would be too extreme. But we will reconsider our idea that GenAI usage in itself can be called a fundamental competency.

We need to safeguard the students’ acquisition of their core competencies in Media Production & Management as a process that can, perhaps even should, take place without GenAI. In this way, they gain the professional foundation and identity necessary to critically assess outputs. That is the beginning of responsible and professionally relevant GenAI usage.

When GenAI is used unreflectively and thus irresponsibly, it deprives our students of some fundamental experiences in their learning processes. It is good that they find it difficult to formulate a problem statement for the first time. It is good that they are overwhelmed by the tone of academic texts. It is good that at first glance they have trouble identifying relevant data points in an annual report. These obstacles make them aware that there is something they haven’t learned yet. This is where GENAI risks giving them easy—possibly even incorrect—answers too quickly. The answer it provides might even be correct, but that is not the point. The point is that their encounters with challenges also confront them with who they are in that situation. They are confronted with the ignorance we all possess. I mean this in the most constructive way. The best products of the Danish media industry—whether they be news articles, films, or computer games—are a confrontation and transformation of the fundamental ignorance we all share.

There is an important formative dimension in the experience of feeling overwhelmed. GenAI must not take that away from them. In the evaluations for both 1st semester courses where we introduced GenAI, some students expressed concern about their perceived dependence on the GenAI tools. They were afraid they were too uncritical of its output and whether it hindered their own learning by taking the path of least resistance. This self-awareness ultimately makes me confident about our students’ future. Doubt and confusion are essential for formation. They are a stumbling block in the path that under no circumstances should be removed by GenAI. They will undoubtedly encounter plenty of doubt, confusion, and fear once they graduate.

Our task is to show them how to keep learning under these conditions—hopefully many years after they have graduated.

Kristian’s piece is a timely reminder: Generative AI isn’t a magic wand — it’s a mirror. And whether you’re a student, a teacher, or somewhere in between, the real test isn’t what the machine gives you — it’s what you do with it.

As we keep charting the messy, magnificent terrain where human creativity meets synthetic suggestion, we’re grateful for voices like Kristian’s — grounded, skeptical, curious, and just idealistic enough to still believe in learning the hard way.

Like what you’re reading?

We’ve got more essays, interviews, and playground experiments on the way — all exploring the evolving relationship between humans and machines in the creative industries.

Subscribe to Prompt Collective to stay in the loop. No spam. Just smart people like Kristian thinking out loud.